Timeline

Travel through 10,000 years of human history to explore how the area known as Bdote by the Dakota became the site of Minnesota’s first National Historic Landmark – Historic Fort Snelling. In this remarkable place, native peoples, trade, soldiers and veterans, enslaved people, immigrants, and the changing landscape all converged to shape the cultural, social, military and political history of Minnesota and the United States.

The shape of water

The Mississippi River was a small tributary 12,000 years ago. It joined the massive Glacial River Warren not far from this spot. Melting glaciers fed both rivers.

The River Warren shrank over time, and the Minnesota River formed. Today, you can visit the place where the rivers join—their confluence—at the tip of Wita Taŋka, or Pike Island.

Wita Taŋka, 2021. Copyright Twin Cities Public Television, used with permission

Bdote: where two waters come together

The land around the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers is sacred. Dakota people call it Bdote, which means “a place where two rivers come together” in the Dakota language.

As long as 10,000 years ago, Native people came here to hunt, fish, and celebrate. They lived in small groups. They traveled with the seasons, gathering food and resources.

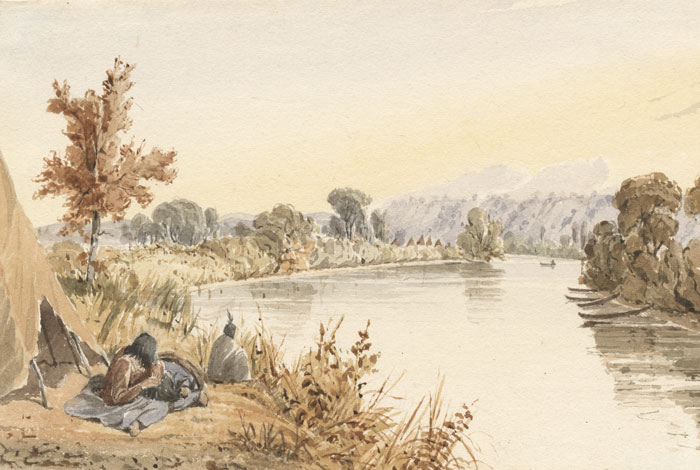

Seth Eastman, The St. Peters River Near Its Confluence with the Mississippi, 1848

Trade along the rivers

Native people traded with each other along the region’s waterways for thousands of years. Europeans arrived in the mid-1600s. After that, French and British traders sought furs from Native trappers. They offered woolen blankets, cotton and linen cloth, metal goods, firearms, fishing gear, and more in exchange.

By 1823, the American Fur Company controlled much of the trade in what would become Minnesota. The company headquarters was located across the river from Fort Snelling, at a place known today

as Mendota.

Henry Sibley house, Mendota, about 1890

A fort on the river

In 1805, the US Army ordered Lt. Zebulon Pike to find a site for a military post along the Mississippi River. He chose land near Bdote. Troops began building the fort in 1819. They used Platteville limestone, quarried from the edge of the river bluff.

Fort St. Anthony was completed in 1825. It was renamed in honor of Col. Josiah Snelling, who supervised its construction.

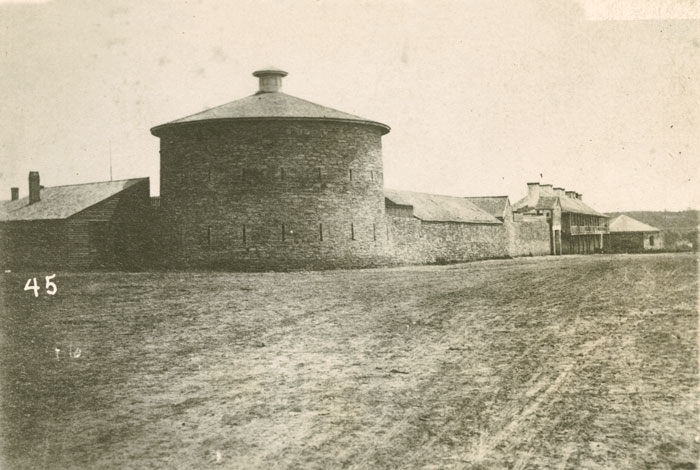

Fort Snelling, 1860. Photograph by Edward Bromley

Enslaved at Fort Snelling

Minnesota was a free territory, but some military officers moved to the fort with enslaved people.

US Army officers were paid to hire servants. Some used enslaved workers instead. The Army allowed this practice, which was not exclusive to Fort Snelling.

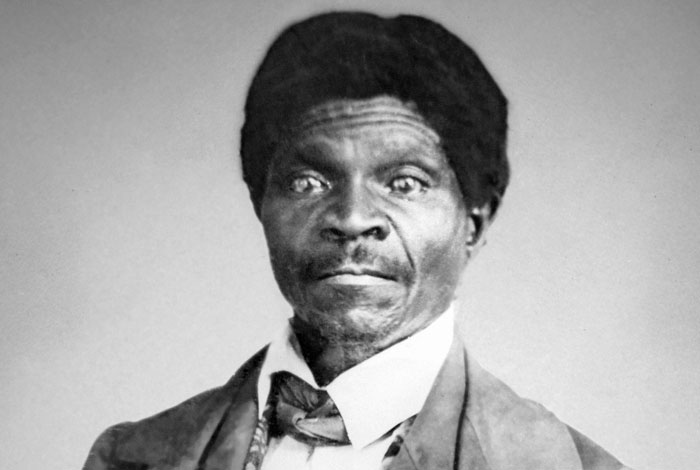

Dred Scott, about 1857

Beyond the walls

The US government incorporated Minnesota Territory in 1849. Two years later, the Treaties of Traverse des Sioux and Mendota were signed. The government acquired millions of acres of land from the Dakota people.

As a result, a flood of settlers and land speculators moved to Minnesota. The territory’s population was 6,077 in 1850. By 1860, it was 172,023, not including Native Americans.

Minneapolis was growing, too. Businesses that harnessed the power of St. Anthony Falls soon lined the Mississippi’s banks.

East side of St. Anthony Falls, Minneapolis, about 1865

Land speculation

Franklin Steele was a land speculator. In 1857, he bought 8,000 acres of land surrounding Fort Snelling. The US government had decommissioned the fort because it had served its purpose.

The financial panic of 1857 meant Steele couldn’t sell the land. He made more than $100,000 renting the land to the government during the Civil War. In 1870, the government bought Steele’s land back.

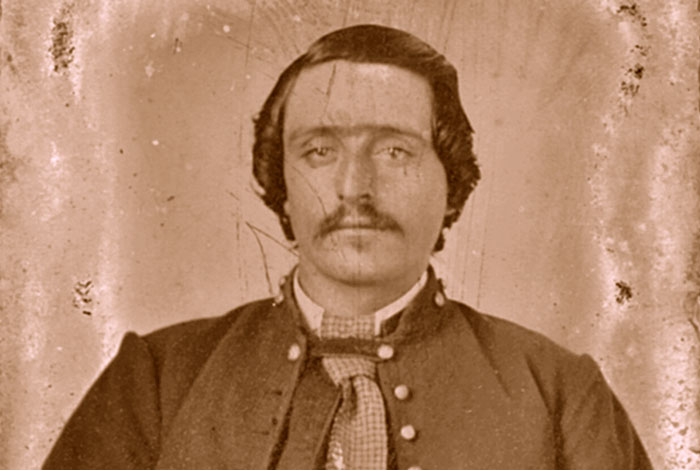

Franklin Steele, about 1860.

The Civil War, 1861–65

On April 12, 1861, the Civil War began. That day, Minnesota governor Alexander Ramsey pledged 1,000 troops from Minnesota. The state was the first to make such an offer.

Fort Snelling was reopened as a place to gather and train recruits. About 25,000 soldiers passed through the fort during the war.

Sgt. Anton Simonet, 1863. Courtesy Therese Scheller

A rush to combat

When the US–Dakota War of 1862 began, parts of four volunteer regiments were forming at Fort Snelling. Col. Henry Sibley rushed four companies to the Minnesota River Valley. Others soon followed.

Many soldiers who joined to save the Union occupied distant forts and were sent to fight Dakota people instead. Others later battled Confederate rebels on Southern fronts, fighting in two civil wars instead of one.

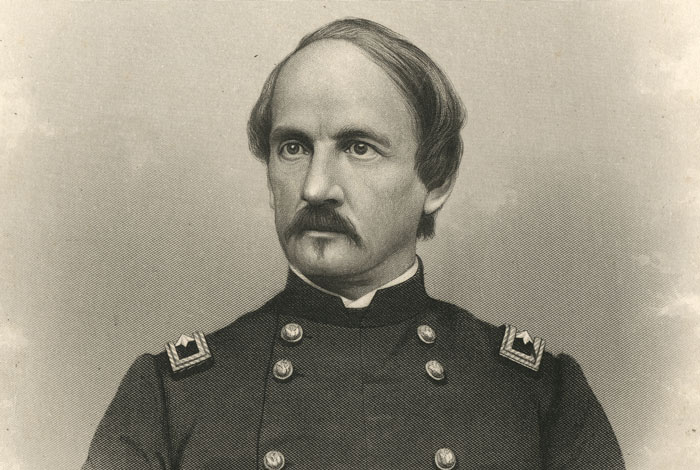

Henry Sibley, about 1862. From a photograph by J. W. Campbell

Expansion after the Civil War

Beginning in 1878, the US Army’s Department of Dakota was headquartered at Fort Snelling. It oversaw all military operations in Minnesota, Dakota Territory, and Montana Territory.

From 1882 to 1888, the 25th United States Infantry Regiment, a segregated African American unit, was garrisoned at the fort.

Company I, 25th Infantry Regiment, at Fort Snelling, 1883

The Spanish-American War

The 3rd United States Infantry was garrisoned at Fort Snelling in April 1898. The Spanish-American War began that month. Troops traveled by train to Mobile, Alabama, then by ship to Cuba. The 3rd fought in battles including San Juan Hill and El Caney. The regiment returned to Minnesota in September.

Spanish-American War recruits at Fort Snelling, about 1898

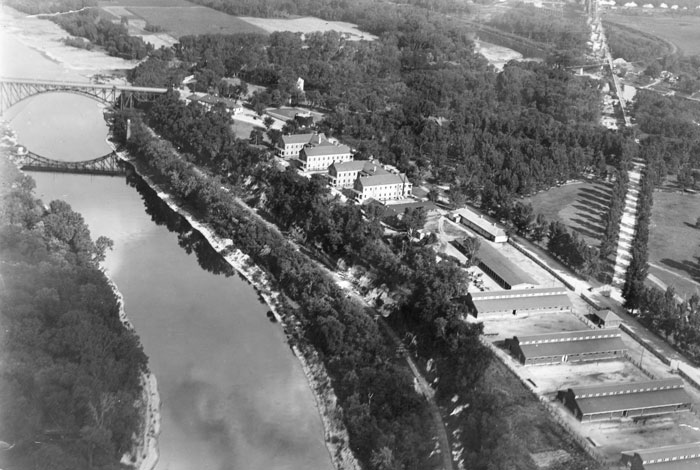

Buildings 17 and 18

In 1905, two state of the art barracks—Buildings 17 and 18—opened at Fort Snelling. Cavalry and infantry troops lived in the barracks through 1946. That year, the Veterans Administration opened an outpatient clinic in Buildings 17 and 18. It closed in 1989.

Today, you’ll find a visitor center, gift shop, exhibits, and classrooms in Building 18.

Aerial view of Fort Snelling, 1925

World War I

In 1917, more than 2,500 soldiers graduated from officer training camps at Fort Snelling. They faced new weapons, like poison gas and machine guns, in World War I.

In September 1918, Fort Snelling was designated General Hospital 29. Workers treated influenza victims and wounded soldiers. They specialized in reconstructive surgery and artificial limbs. The war officially ended on June 28,1919 with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. The hospital closed a few weeks later.

Wounded soldiers rehabilitating at Fort Snelling, 1919

The Civilian Conservation Corps

The Great Depression left millions of men unemployed. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was established in 1933 to help these men.

At Fort Snelling, CCC recruits trained to work in the forests of northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. Throughout the 1930s, thousands of men joined CCC companies formed at the fort.

CCC workers at Fort Snelling, 1933

World War II, 1941–45

More than 300,000 men and women joined the US military at Fort Snelling during World War II. They were at the fort for a short time before shipping out for basic training. Six thousand soldiers also studied Japanese at a military language school.

Soldiers at the fort enjoyed dances and socials, swimming, and golfing. The Red Cross ran a movie theater and a library at the fort.

Servicemen receiving shots at Fort Snelling, about 1940

The end of an era

A year after World War II ended, Fort Snelling was decommissioned as an active military post. Post Commander Harry J. Keeley explained: Military posts of the future peace time Army must accommodate about 30,000 men. . . . So Fort Snelling must go.

The Veterans Administration (VA) took over Fort Snelling. The VA ran an outpatient clinic in Buildings 17 & 18 until 1989.

Final retreat at Fort Snelling, October 14, 1946. St. Paul Dispatch–Pioneer Press photograph

Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport

Advances in air travel happened during World War II. After the war, Twin Cities leaders wanted to build a major regional airport.

The Metropolitan Airports Commission (MAC) proposed expanding Wold-Chamberlain Field. The small airport, dating from 1920, spanned parts of Minneapolis and Richfield. After much negotiation, MAC acquired 700 acres of land from Fort Snelling by 1956.

Wold-Chamberlain Field, 1940

Historic Fort Snelling

In 1956, the Minnesota Highway Department announced plans to build Highway 55. The route cut through the remains of Fort Snelling. After citizens voiced their opposition, the site attracted preservationists’ notice.

In 1960, Fort Snelling became the state’s first National Historic Landmark. Five years later, the Minnesota Historical Society began restoration.

Archaeological excavation at Fort Snelling, 1974. Photograph by Charles Diesen

Fort Snelling State Park

Dedicated in 1962, Fort Snelling State Park covers 1,700 acres. Its recreational and natural history trails attract visitors of all ages.

The park includes Wita Tanka (Pike Island) and the site of the concentration camp built after the US–Dakota War of 1862. These important sites are commemorated at the park.

Wokiksuye K’a Woyuonihan memorial, Fort Snelling State Park, 2022. Photograph by Therese Scheller

Fort Snelling today

Located near both the Minneapolis–St. Paul International Airport and the Fort Snelling National Cemetery, Historic Fort Snelling is still a hub of commerce, travel, and military service, much as it was in 1825.

The National Park Service, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the City of Minneapolis, the US Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines; Veterans Administration; and Minnesota Air National Guard all manage nearby sites.

Historic Fort Snelling, 2019