The Expansionist Era (1805-1858)

In 1805 the United States Army ordered Lieutenant Zebulon Pike to explore the Mississippi River and select sites for potential military posts. When he arrived at the junction of the Mississippi and St. Peters (present-day Minnesota) rivers, Pike made an agreement with several Dakota representatives to acquire land on which he promised a US fort and government "factory" (trading post) would be built. Pike drew up a document, which included an article granting the US land for military posts at the mouth of the St. Croix River and at Bdote, up the Mississippi River to St. Anthony Falls. Of the seven Dakota leaders present, only two signed the document.

There were several problems with the agreement. The president of the United States had not authorized Pike’s expedition, and therefore the army lieutenant had no legal authority to negotiate a treaty with any Native Americans. The US Senate did not discuss the agreement until 1808. The Senate unilaterally set the amount of land granted by the treaty at over 51,000 acres at the St. Croix River and over 100,000 acres at Bdote, extending north up the Mississippi. Once the acreage was determined, the Senate set payment for the land at $2,000, though Pike had estimated its value at $200,000. No Dakota were present to agree to these terms. After the Senate ratified the treaty, President Thomas Jefferson did not proclaim it, which was standard procedure at the time. For these reasons, the “treaty” that set the legal groundwork for the construction of Fort Snelling was invalid. Even so, the US government continued to act as though it was a legally binding document.

The first troops arrived in 1819 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Leavenworth and began construction on the stone fort the following year. Colonel Josiah Snelling arrived in 1820 to supervise construction, and by 1825 the fort was completed. Initially called Fort St. Anthony, the post was renamed "Fort Snelling" by the US War Department in honor of Snelling’s efforts.

Bdote, which is important as a spiritual place and a meeting ground for Dakota people, was also the perfect strategic location for the US to fulfill its colonial aims. Fort Snelling was intended to dissuade the British from any further incursions into the Northwest and to stamp out British influence in the booming fur trade. The US intended to exploit the region’s resources for economic gain. The soldiers at Fort Snelling were tasked with keeping unauthorized people off Dakota and Ojibwe land so the fur trade could continue until the land could be acquired through treaties. Finally, the United States sought to mediate the complex relationship between the sometimes clashing Dakota and Ojibwe. Peace between the two peoples would mean an uninterrupted flow of furs and tax revenue for the US government. The Dakota were far more powerful than the small garrison at Fort Snelling, but construction of the fort marked a seminal moment in the invasion of Dakota lands.

Fort Snelling remained in service for nearly 40 years, until 1858 when Minnesota became the 32nd state. By then the US government had established forts further west and Fort Snelling was no longer considered necessary, so the post was officially closed later that same year. The fort and its military reservation was purchased from the government by Franklin Steele, a local entrepreneur and former Fort Snelling sutler, who intended to plot and sell off lots for a new city named "Fort Snelling." During this time, the post was turned into pasture and Steele's sheep were frequently seen grazing on the fort's old parade ground.

Resources

- Beeson, Lewis ed. Snelling, Henry Hunt. Memoirs of a Boyhood at Fort Snelling. Minneapolis: Private Print, 1939.

- Case, Martin W. “‘Pike’s Treaty’—One Bdote Area Myth.” Bdote Memory Map, March 14, 2010.

- Cassady, Matthew and Peter J. DeCarlo. "Fort Snelling in the Expansionist Era, 1819–1858." MNopedia, May 20, 2015.

- DeCarlo, Peter. Fort Snelling at Bdote: A Brief History. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

- Hall, Steve. Colossus of the Wilderness. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987.

- Hanson, Marcus L. Old Fort Snelling, 1819–1858. Minneapolis: Ross & Haines Inc., 1958.

- Jones, Evan. Citadel in the Wilderness: The Story of Fort Snelling and the Northwest Frontier. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1966.

- M683, Josiah Snelling Papers, 1779–1828

Manuscript Collection on microfilm, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Photocopied letters written by Josiah Snelling. - Kier, Samuel Martin. Two Centuries of Valor: The Story of the 5th Infantry Regiment. Pacific Grove, CA: Park Place Publications, 2010.

- Kunz, Virginia Brainard. “Colonel Snelling’s Journal: Orders, Letters, Lists of Possessions.” Ramsey County History 6, no. 1 (Spring 1969): 9–11.

- M35, M35-A, P1203

Lawrence Taliaferro Papers (PDF), 1813–1868

Manuscript Collection, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul

Description: Papers relating to Taliaferro’s tenure as Indian Agent at St. Peters near Fort Snelling from 1820 to 1839. - Prucha, Francis Paul. Broadax and Bayonet: The Role of the United States Army in the Development of the Northwest, 1815-1860. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1953.

- Westerman, Gwen, and Bruce White. Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert. North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

- Ziebarth, Marilyn, and Alan Ominsky. Fort Snelling: Anchor Post of the Northwest. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1970.

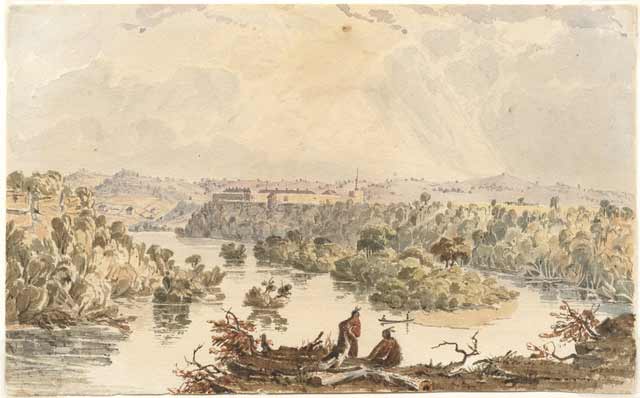

Distant view of Fort Snelling at Bdote, painted by Seth Eastman, 1847–1848. Source: MNHS Collections.

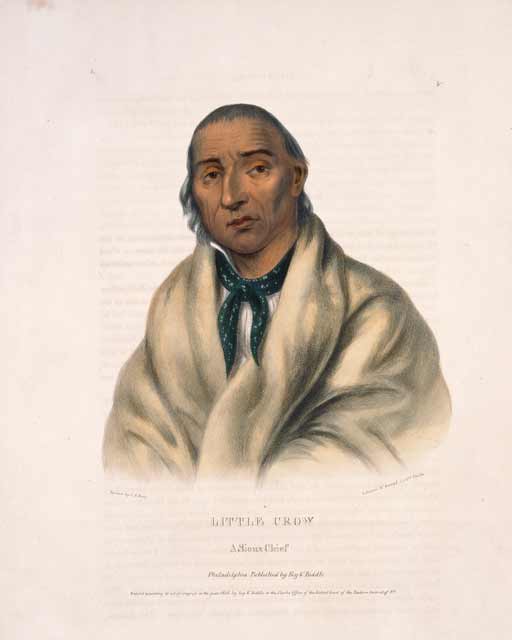

Cetan Wakuwa Mani (Hawk that Hunts While Walking) or Little Crow, leader of the Bdewakantunwan Dakota village of Kap’oza. Lithograph by Charles Bird King, 1836. Source: MNHS Collections.

Colonel Josiah Snelling, ca. 1818. Source: MNHS Collections.

Fort Snelling at Bdote, painted by John Casper Wilder, ca. 1844. Source: MNHS Collections.