"We Left Camp Before It Was Light in the Morning..."

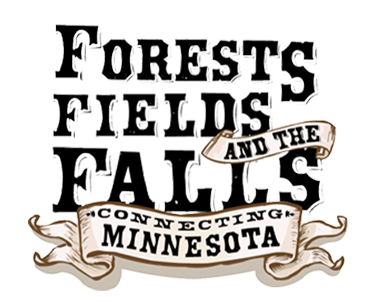

Crew with horses skidding logs out of the forest, 1885.

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Location No. HD5.32 r10, Negative No. 78640

"... and didn't get back until after dark at night. I always come in as hungry as a she-bear with cubs and was ready for anything the cook had on the table."

—Louie Blanchard

Walker D. Wyman and Lee Prentice, The Lumberjack Frontier: The Life of a Logger in the Early Days of the Chippeway, Retold from the recollections of Louie Blanchard (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969).

"But in Spite of These Drawbacks ..."

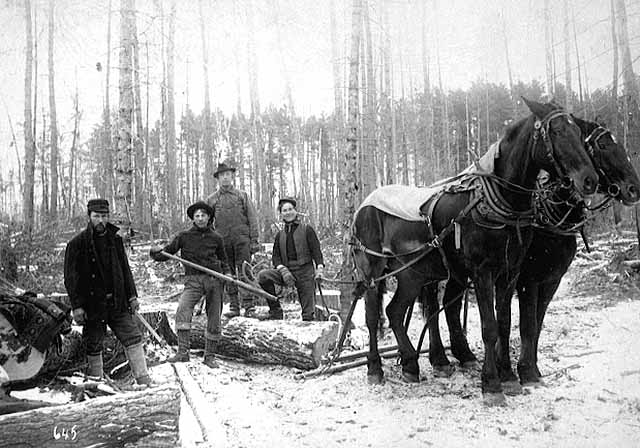

Lumberjacks sawing tree into logs, ca. 1905.

Photographer: Arthur A. Richardson

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Location No. HD5.22 r19, Negative No. 70015

"... I believe I enjoy the work better than any I ever did before. Sawing to my notion is the best job in the woods, the time passes quickly, and although it is very cold, from zero to 30 below so far, you don't notice it so much in the timber and what I eat at home would be scarcely a light lunch for me here. There is no boss over you while you work, you go into the woods and saw all day and give in you logs at night. We saw from 80 to 110 according to the size of the timber.... It is steady but if you know how to saw and have a good partner it is not hard."

—Horace Glenn in letter to his parents, 1901

Andrew W. Glenn and Family Papers.

Minnesota Historical Society Manuscript Collection. A/.G558.

Why Log in Winter?

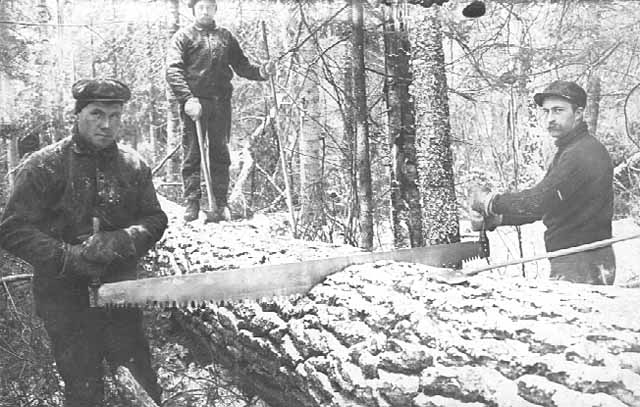

Two undercutters at work in the pineries of Minnesota. The undercutters notch the tree on a certain side to make it fall in a certain direction. (1880)

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Runk 33

Winter ice, spring floods, sunken sap, and available labor are some of the biggest advantages to winter. (Insects and thick grasses are some of the disadvantages of summer.)

After the tree is cut, it still has to be taken out of the forest. It's easier to drag a log through snow and slippery ice than through dirt and mud. Loggers took advantage of this: they built roads with ruts which they would fill with water and let freeze, creating ice-roads from the trees to the river.

At the end of the winter, all of the logs are waiting by the river. When it floods, the river lifts up the logs and carries them downriver to the sawmills. If logging was done in the summer, when rivers are low, the log drive wouldn't work.

Also in summer, a tree is more active, with sap flowing through its walls to carry food. In winter, the tree goes into a sort of hibernation and all the sap drops to its roots. The trunk of the tree now has less sap to gum up saws and weighs less when it's cut, making it easier to move.

Finally, the men in a lumber camp usually have other work the rest of the year. The logging camp would have a hard time finding workers in the busy summer, but in winter farmers and other laborers are looking for jobs.

Who Were These Men?

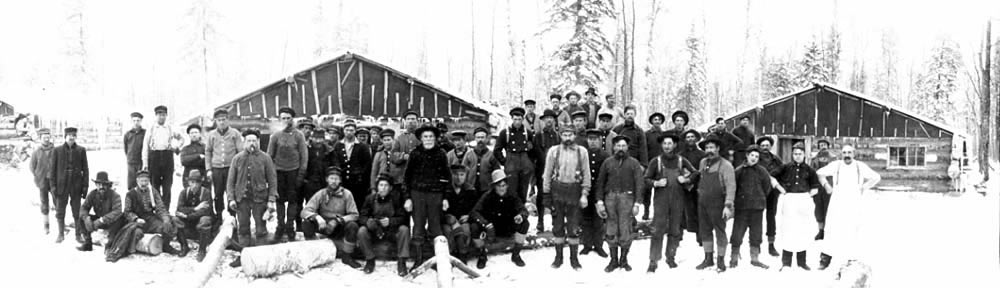

Logging crew, Bemidji, ca. 1900-1920

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, AV 2001.185

"They were principally Scandinavians; but there were also some French, Finns, Poles, and about 10% native Yankee stock."

Joseph DeLaittre, A Story of Early Lumbering in Minnesota (Minneapolis: DeLaittre Dixon Co., 1969).