What Is That Machine?

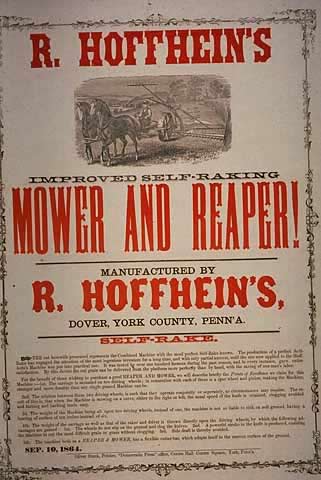

R. Hoffhein's Mower and Reaper! (1864)

Minnesota Historical Society Poster Collection, SA2.5 a7

Introduced in the 1850s, self-raking reapers cut the wheat and gathered it into bunches to be bound and threshed. Fifty years earlier, reaping was done by hand with the centuries-old technology of the sickle. The horse-drawn reaper appeared in the 1830s. It cut the grain faster and better, but still required a worker with a rake to gather the wheat into useful bundles.

Raking was difficult work. In 1861 a farmer near Hastings, Minnesota, described his feelings in his diary:

"Oh, how racked in body I feel. Sore and lame all over my body; fingers cut up etc. It is absolutely hard work to follow a reaper."

Levi N. Countryman papers, 1858-1862.

Minnesota Historical Society Manuscripts Collection

Threshing

Threshing rig of C. R. Chrislock, Goodhue County, 1880-1889.

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Location no. SA4.6 r70 Negative no. 45655

"As soon as the grain was hard enough, the [threshing] machine was moved into the centre of the field and 'set.' Six teams with their drivers, three pitchers in the field, and two band-cutters, one on each side of the feeder, were necessary to supply the wants of the wide-throated monster. It was stacking and threshing combined. A wagon at each "table" kept the cylinder busy chewing away, while the other teams were loading. At the tail of the stacker, a boy with a pair of horses hitched to the ends of a long pole hauled away the straw and scattered it in shining yellow billows on the stubble, ready to be burned."

—Hamlin Garland, 1899.

Hamlin Garland. Boy Life on the Prairie (NY: Harper & Brothers, 1899).

What Happens to the Wheat after Harvesting?

Threshing rig of C. R. Chrislock, Goodhue County, 1880-1889.

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Location no. SA4.6 r70 Negative no. 45655

"As soon as the grain was hard enough, the [threshing] machine was moved into the centre of the field and 'set.' Six teams with their drivers, three pitchers in the field, and two band-cutters, one on each side of the feeder, were necessary to supply the wants of the wide-throated monster. It was stacking and threshing combined. A wagon at each "table" kept the cylinder busy chewing away, while the other teams were loading. At the tail of the stacker, a boy with a pair of horses hitched to the ends of a long pole hauled away the straw and scattered it in shining yellow billows on the stubble, ready to be burned."

—Hamlin Garland, 1899.

Hamlin Garland. Boy Life on the Prairie (NY: Harper & Brothers, 1899).

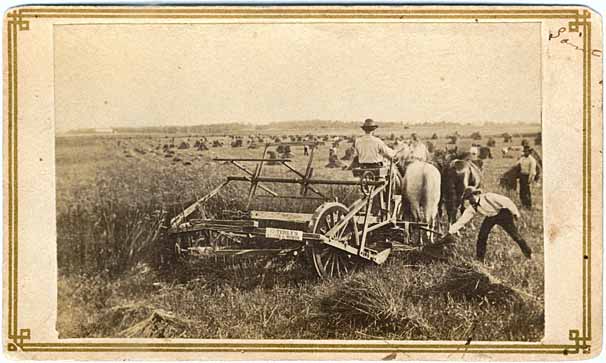

Machinery, Productivity, and Debt

Esterly reaper in operation in grain field, St. Paul, 1860.

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, SA4.52 r59

"In 1800 farmers planted seed by hand and harvested with a scythe and cradle. By 1900 4-horse gang plows turned the soil over four furrows at a pass, grain drills planted the seed, and self-binding reapers brought in the harvest."

—David Stevens "The Mechanization of Farming, 1800-1920"

Continuing advances in technology changed farming from the 1860s to the end of this period. New horse-drawn plows, reapers, threshers, and other machines make it possible to grow more food per acre with less labor. Farmers could then make more money from the same amount of land.

On the other hand, machinery was expensive and farmers didn't normally have much money. They took out loans to buy the latest gadget; or, with new capacity they would take on a mortgage for more land. A bad year could leave them in serious debt. The Carpenter family was always burdened by debt:

"If we had had an ordinarily good crop we could have been entirely out of debt this last fall. We had 150 acres of wheat, but it did not even pay expenses. We have to buy our flour, paying $3.50 a hundred. "

—Mary Carpenter letter, Jan 1, 1882

"The grain is looking very fine, if nothing comes to destroy it. George has 260 acres in, 200 of it rented land. We hope if the prices are good to get out of debt next fall."

—Mary Carpenter letter, July 22, 1883

"It is the same old thing debt & being trammeled on account of it....

"If the children do well, & keep out of debt I shall have good cause for gratitude whether we ever are even with the world or not."

—Mary Carpenter letter, March 31, 1887

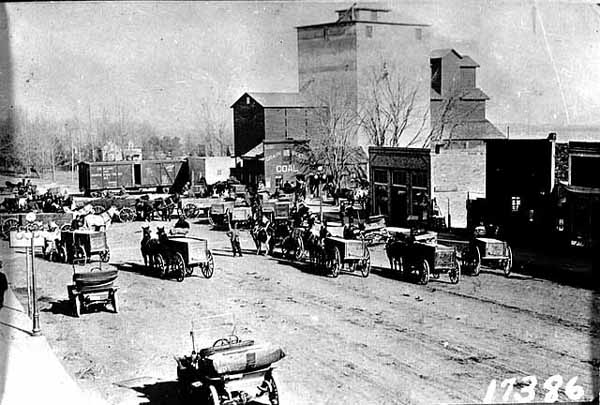

Bonanza Farms

Harvesting on James J. Hill's farm at Northcote, 1901.

Minnesota Historical Society Photograph Collection, Location no. SA4.52 p45, Negative no. 10083

The same rich soil, access to rail transportation, and demand for spring wheat that attracted settlers also attracted big business in the 1870s and 1880s. Major stockholders in the failed Northern Pacific railroad found themselves as owners of thousands of acres (settlers had to live on the land five years to get 160 acres). They hired managers, bought expensive machines, and took on large crews of temporary labor to work the fields.

Bonanza farms accounted for only 2% of the midwest's farms, but they efficiently produced millions of bushels of wheat for Minneapolis's hungry mills. They also quickly cut open the prairie and robbed it of essential nutrients, partially leading to the decline of the giants in the 1890s.

"The whole summer of 1887 I worked on a section of Dalrymple's immense farm in the Red River Valley of the North. Besides myself there were two other Norwegians, a Swede, ten or twelve Irishmen, and a few Yankees. We were twenty-odd men all told on our little section—but we were a mere fraction of the hundreds of laborers on the whole farm.

The prairie lay golden-green and endless as a sea. No buildings could be seen, with the exception of our own barns and sleeping shed in the midst of the fields. Not a tree, not a bush grew there—only wheat and grass, wheat and grass, as far as the eye could see....

No birds flew overhead; there was no movement except the swaying of the wheat in the wind; no sound but the eternal chirrup of a million grasshoppers, singing the prairie's only song....

We worked a sixteen-hour day during the wheat harvest. Ten mowing machines drove after each other in the same field, day after day. When one field was finished, we went to another and laid it down as well. And so onward, always onward, while ten men came behind us and shocked the bundles we left. And high on his horse, with a revolver in his pocket and his eye on every man, the foreman sat and watched us...."

—Knut Hamsun

Knut Hamsun, "On the Prairie: A Sketch of the Red River Valley" (translated by John Christianson), in Minnesota History, Sept, 1961. (Originally published in 1903 as "Pa Praerien" in Kratskog).